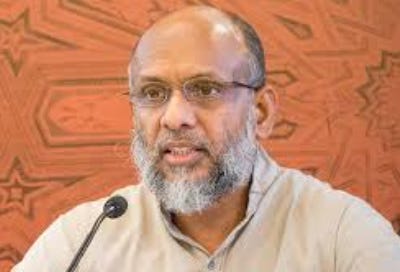

I haven’t met him, yet his writing has captivated me. He’s critical, but his criticisms are sincere and driven by a desire to better society. His oeuvre in Arabic and Urdu is in a category of its own – an eclectic mix of multiple genres: travelogues, obituaries; essays on social reform, education, politics, language, literature, Quran, hadith, fiqh, history and so much more – and, I sincerely hope, that his writings remain as a guiding light for generations to come.

Despite only living a mere eighty miles from my native Birmingham, I haven’t had the good fortune of meeting Dr Akram Nadwi – more so because of my recluse nature rather than his being inaccessible. But I have read his works. And I read them with great enthusiasm.

In Urdu and Arabic his words dance on the page. With every sentence you’re left hanging on to each word, eagerly awaiting the next, moving from sentence to sentence, paragraph to paragraph, page to page, only to be left mesmerised by the whole experience. They’re not words on a page; they’re a magician’s sorcery. His quiver of phrases is full to the brim of literary and rhetorical devices that work like the charm of the Pied Piper of Hamelin. The Prophet Muhammad, Allah bless him and grant him peace, once remarked: ‘Indeed some speech is as effective as sorcery’ (Bukhari). This is most aptly embodied in Dr Akram Nadwi’s writing.

In English literature, one way of viewing modern novelists is to divide them into two categories: the engaged and the unengaged. The engaged have something they want to tell us, often something about the current state of society. They’re not necessarily propagandists, or even message bearers, but they have something on their minds which they wish to convey to us. Some specific view of the world based on their insight and which they wish to convey to us by any means necessary. To this category belong, Orwell, Huxley and Swift, different as they are in other respects. On the other side we have the unengaged. They have very little to do with changing people’s minds. But they do care about their own symbolic structures and how they convey these through an aesthetic of belles-lettres. To this category belong Borges and Nabakov.

Yet the bundle of flesh and bones personified in the personage of Dr Akram Nadwi, is both an engaged and unengaged writer: his strong-willed temperament trying to remedy a social wrong on one side; and an eloquent portrayal of these ills, vices and their remedies on the other.

Need I remind the reader, I’m not his student, nor a disciple. As I’ve stated above, I have never met him in person. But my praise for his works is independent and sincere – I’m an innocent bystander of sorts - one who has read, appreciated, admired and felt not only the sincerity which imbibes his works, but also his insight, which at times, leaves one thinking: ‘hmmmm…an interesting point that.’

He’s not your average maulvi sahib in your local mosque. He’s a well-read individual familiar with the literature, culture and traditions of Islam - of the Arabic east and west - of the Indian subcontinent, and to some extent, ever since he came to live in the UK, of European and Western culture.

But he’s also not an ivory tower person. He’s practical. And his fatawa bear the hallmark of someone who is aware of the social and practical implications of his edicts: facilitating ease where necessary, and avoiding a mere repetition of age-old rulings that do not bear any practical benefit to the twentieth century. Yet, at the same time, he’s not a complete modernist either. He’s a fusion of the past and present; an amalgamation of the old and new - a blend of traditionalism with practical realism.

It is this very practical realism that makes him markedly different from the well-meaning orator on the pulpit who thinks that the world will be perfect if you start wearing the kurta or a jubba and grow your beard to a fistful’s length.

He laments the situation of Islamic seminaries today. He loathes their insistence on dogmatism, intolerance and narrow-mindedness. ‘The madaris of today are mere factory farms of sectarianism’, he writes in a Telegram post. Yet he realises these madaris will not change overnight and so, his practical realism tells him that, given the existing mindset of society, certain evils cannot be remedied.

I’ve found my own opinions coinciding with his many a time.

Dr Akram has a passion for the thought of Shah Waliullah and especially his magnum opus, Hujjatullah al-Balighah - so too do I. He is of the opinion that one can wipe over cotton and nylon socks for ablution - so too do I. He appreciates Arabic and Urdu literature - so too do I.

In Arabic literature, like me, he recommends one begin with an immersive method; and not to begin by the current grammar and translation method as is taught in the seminaries of the Indian subcontinent and their ancillary institutions in the UK & USA. This immersion is akin to a ‘language bath’, whereby the students gain proficiency in all four skills: reading, writing, speaking and listening, simultaneously.

True, grammar is important and necessary, but not for the novice. The novice needs immersion. To hear, listen, speak, read and write. The focus in these initial stages is not on accuracy, but fluency. Accuracy is gained at a later stage.

In this regard, he favours the syllabus prepared by the Umm al-Qura University in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. I however find that it’s content is restricted to religious literature and this curbs its benefit, which is why I prefer the At-Takallum series which has also won an award for the best Arabic language coursebook for non-native speakers.

To develop a good literary taste in Arabic prose, once one has a good grasp of grammar and morphology, Dr Akram Nadwi emphasises the importance of Kalilah Wa Dimnah. A book much like Aesop’s Fables where the characters are depicted as animals, and the moral of the story is the ultimate goal. Kalilah Wa Dimnah, originally written in Sanskrit, and translated into Arabic from the Pahlavi translation by Abdullah b. Muqaffa' tells engaging tales about cats and mice, storks and crabs, tortoises and geese, owls and crows, and princes and ascetics. The stories work as illustrations of human predicaments. Muqaffa’s translation is a translation par excellence. Much can be gained by imitating his style in Arabic. It is not only a natural style, plain and easy to read, but it also has an elegance that imbibes every sentence. Dr Akram Nadwi, following the footsteps of his Shaykh, Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi, read this work 40 times so as to be influenced by the style of the author. Any serious student of Arabic literature can see this influence quite plainly in Dr Akram’s works.

Once one has read and re-read Kalilah Wa Dimnah multiple times, then one should proceed towards the two anthologies: al-Manthurat by Rabi’ Nadwi, and to the Mukhtarat of Abul Hasan Nadwi. Both these works will not only acquaint one with the best stylists of Arabic but also see the chronological stylistic development of the Arabic language from the 6th century up until the twentieth.

Thereafter, one should read the works of the great stylists, which include, al-Jahiz, Taha Husain, Manfaluti, Tantawi, Rafi'i, A.H. Nadwi - and, dare I add - Akram Nadwi.

Similarly, to develop a good literary taste for Arabic poetry, one must wrestle with the ancient poets of Arabia: both pre-Islamic and Islamic.

Starting with the pre-Islamic poets: al-Mu‘allaqat al-‘Ashr, subsequently moving on to the collected works of Imrul Qays, Nabigha and Zuhayr b. Abi Sulma. One should read the al-Mufaddaliyat, al-Asma‘iyyat, and a work one cannot do without, is the Diwan Hamasah of Abu Tammam al-Buhtari.

The early Islamic poets include: the collected works of Jarir, Farazdaq, al-Akhtal, Dhu al-Rumma, Umar b. Abi Rabi‘ah.

The Abbasid poets include the likes of: Bashar b. Burd, Abu Nuwas, Mutanabbi, and al-Sharif al-Radi.

The Andalusian poets include the collected works of: Ibn Zaydun and Ibn Khafajah.

It is only after one has spent a decade reading, annotating and summarising the works of these authors that one will be able to see a marked difference in one’s writing and an appreciation of good literature.

In Urdu literature he emphasises the importance of reading the poetry of: Mir Taqi Mir, Mir Dard, Ghalib, Iqbal and Akbar Allahabadi. In Urdu prose, it’s: Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan, Nazir Husain, Abul Kalam Azad, Shibli and Abdul Majid Daryabadi.

I hope to review some of Dr Akram’s works later, God willing, but what I wish to focus on today is a collection of essays in Arabic entitled Imlā al-Khāṭir, or ‘Dictated Thoughts’. A pot-pouri of essays, or opinion pieces, numbering around sixty in total. They’re mostly written in a dialogic style of students asking their teacher puzzling questions which the esteemed teacher then answers through his penetrating insight. This figure of speech serves as a tool in engaging the audience, guiding their thinking and emphasising key points.

In one of the essays he describes Eid in his ancestral village in Jaunpur, India. Immediately we are transported to a time before i-phones, the internet and social media. The simplicity of village life in rural India rush before our eyes. Villages consisting of mud-hut houses, sprouting sugarcane fields, mustard leaves, black heavy limbed water-buffaloes wallowing during the day, come and go on the pages before us. He tells of us his mother dressing him in his best clothes on Eid day and then sending him to his grandparents so that their prayers can ward of the evil-eye.

He writes in Arabic:

فإذا دعا جدّاي لي بدعوتهما الصالحة بلغ الجذل مني أقصاه و أيقنت أني محفوظ من كلّ سوء و معتصم بملاذ آمن

You see the world through the eyes of a child. The simplicity with which he views the world and the prayers of the most dearest people to him make him believe that he is truly immune from every evil.

In another essay he speaks about the the pre-Islamic poets and how they’re to be preferred over modern day physicists and scientists. The pre-Islamic poets led a plain and candid life. They pass ruins and immediately are called to a halt, they reminisce over past lives once lived. Old passions rekindled, beloveds re-remembered and almost without cessation, tears fill their eyes. But not with the archaeologist. Their whole enterprise is driven by seeking out old ruins. But not a single tear is shed. This is where the pre-Islamic poets part pathways with the scientist.

Imrul Qays says:

قِفَا نَبْكِ مِنْ ذِكْرَى حَبِيبٍ ومَنْزِلِ

بِسِقْطِ اللِّوَى بَيْنَ الدَّخُول فَحَوْملِ

فَتُوْضِحَ فَالمِقْراةِ لمْ يَعْفُ رَسْمُها

لِمَا نَسَجَتْهَا مِنْ جَنُوبٍ وشَمْألِ

Zuhayr b. Abi Salma states:

أَمِن أُمِّ أَوفى دِمنَةٌ لَم تَكَلَّمِ

بِحَومانَةِ الدُرّاجِ فَالمُتَثَلَّمِ

وَدارٌ لَها بِالرَقمَتَينِ كَأَنَّها

مَراجِعُ وَشمٍ في نَواشِرِ مِعصَمِ

The nostalgia with which both poets view these ruins recalls their deep connected roots not only to the former dwellers but also to the place. Every stone, every ash-coloured rock, indeed every gazelle dropping also indicates that there once lived a beautiful damsel here once and now she’s gone.

In another essay in Imlā al-Khāṭir, Dr. Akram Nadwi, laments the ‘language’ spoken by the immigrant workers from the Indian subcontinent in the Emirates. His passion and love for the Arabic language is clearly seen when he refuses to call it a ‘language’, let alone Arabic. He says:

أبيت أن أسمّيها عربية، و لعنت من سمّاها هذه التسمية، و بالغت في سبّه و شتمه و تجديعه و تشنيعه، بل أبيت أن أسمّيها لغة. و إنها لوصمة عار على جبين البشرية، يفصل الحكماء اليونان و أتباعهم الإنسان عن سائر الحيوان بالنطق، فإن كان ما يلفظ به هؤلاء نطقًا، فما لبني آدم فضل على البهائم

Dr Akram Nadwi is a great asset for Muslims. I fear, however, that the English speaking Muslim community cannot truly appreciate his genius because English is not his forte. His writing excels in Arabic and Urdu, but not so in English. There have been attempts at translations in the past, and more recently AI assisted translations too, but the harsh reality is that they do not do justice to his work. And if there was one criticism I would raise against him, it would be that someone who appreciates the language and arts should have recognised the great asset he could have utilised through the language that has become the lingua franca of the world. The language of the English Bible, of Shakespeare, of Milton, of Dickens, of the Bronte sisters, of Austen, of Wordsworth, of Coleridge and Keats. How wonderful the world would have been if he had developed a good literary pen in the English language!

I will return to writing reviews of some of his other works in the future, but for now this should suffice.

Shazad Khan

Birmingham, UK

Excellent read - exposition of the writings of a contemporary giant mA.

The reading list for developing one's proficiency in Arabic is greatly appreciated!